Airborne wind energy (AWE) is the conversion of wind energy into electricity using tethered flying devices. Some concepts combine onboard wind turbines with a conducting tether, while others convert the pulling power of the flying devices on the ground. Replacing the tower of conventional wind turbines by a lightweight tether substantially reduces the material consumption and allows for continuous adjustment of the harvesting altitude to the available wind resource. The decrease in installation cost and increase in capacity factor can potentially lead to a substantial reduction of the cost of wind energy. Wind at higher altitudes is also considered to be an energy resource that has not been exploited so far.

Table of Contents

Historical perspective

In the 1930s, German engineer and wind energy pioneer Hermann Honnef developed concepts for gigantic wind power plants with several rotors supported by towers that were several hundred meters high.1,2 Around the same time, German engineer Aloys van Gries, who in 1921 had authored a standard textbook on aircraft structures,3 filed patents for using kites to deploy wind turbines at higher altitudes.4,5,6 Van Gries essentially proposed to combine trains of large lifter kites that had been used by many observatories around the world for high altitude measurements,7 with the emerging wind turbine technology. Precisely this idea of harvesting high altitude wind was concretized half a century later, during the 1970s energy crisis, by space age pioneer Hermann Oberth, who proposed it as an alternative to fossil fuels and nuclear power.8,9 At the same time, the team of Bryan W. Roberts at the University of Sydney developed and tested quad-rotorcraft for harvesting high-altitude wind energy,10 while Miles L. Loyd, an American engineer working at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, laid the foundation for quantitative analysis of AWE systems. In his seminal article,11,12 Loyd compared the pulling power of a kite that is moving only in the direction of the tether with the maximum power of a kite that is additionally flying crosswind maneuvers. This comparison is summarized by the following diagrams showing the power harvesting factor $\zeta = P/(\Pw S)$ as a function of the tether reeling factor $f=\vt/\vw$ for different values of the lift-to-drag ratio $\CL/\CD$ of the kite.

In this nondimensional representation, $\vw$ is the wind velocity, $\vt$ the tether deployment velocity, $\Ft$ the tether force, $P=\Ft\vt$ the pulling power, $\Pw=½\rho \vwexp{3}$ the wind power density and $S$ the wing surface area. For simplicity the aerodynamic lift coefficient $\CL$ is set here to 1. The two diagrams show that crosswind operation of a kite greatly increases its power output and that this increase is amplified with the lift-to-drag ratio. For higher lift-to-drag ratios the increase is more than two orders of magnitude.

For the crosswind kite, Loyd computes the maximum harvesting factor as $$\zetaopt=\frac{4}{27} \frac{\CL^3}{\CD^2}$$ which occurs at the reeling factor $$\fopt=\frac{1}{3}.$$ Comparing the two diagrams, it is obvious that cross-wind operation drastically increases the electricity output.

Loyd also investigated onboard conversion for a kite flying crosswind at constant tether length and concluded that the performance is similar to ground-based conversion. The two different conversion modes are illustrated in the following figure, where $\vvkt$ and $\vvkr$ are the tangential and radial components of the kite velocity $\vvk$.

Loyd predicted that a large tethered aircraft could theoretically produce from 7 up to 45 MW of electrical power, which was far beyond what wind turbines at these times could generate. On the other hand, many of the effects neglected in the idealized analysis, such as the mass of the kite and tether as well as the aerodynamic drag of the tether, would significantly reduce the available power. Also, flying systems are generally more complex than wind turbines on the ground, with more degrees of freedom, possible sources of failure and more severe consequences of failures. The automation of flight operation, particularly launching and landing, is challenging and substantial advances in material science, control technology and mechatronics would be required before practical implementations could be realized. It would in fact take another 20 to 25 years and the imminent threat of global warming to trigger a renewed interest in AWE as a source of renewable energy, eventually leading to networked R&D activities and an emerging industry.

Development as an industry

Just before the turn of the century, TU Delft professor and former astronaut Wubbo Ockels presented a high altitude wind energy concept based on a cable loop that was running from a ground station into the sky.13 Driven by kites attached at regular intervals, the mechanical net pulling power in the loop was to be converted into electricity at the ground. Although this “laddermill” was only a conceptual idea the persistent effort of Ockels would lead to the establishment of a research group in 2004, spinning off two pioneering companies, Ampyx Power (2007) and Kitepower (2016). The increasing number of institutions involved in AWE worldwide is illustrated in the following diagram.

Included are only those academic groups or commercial teams that have been actively involved in research and development of entire AWE systems - individual researchers or inventors, component suppliers and investors are not included. From 2008 to 2010 the community experiences a substantial growth and in 2018, the R&D landscape comprised more than 60 institutions, which is illustrated in the following map.14

The main contributing regions are North America and Europe, with the difference that the activities in the US are dominated by Makani, an ARPA-E-supported startup that became a Google moonshot project, while in Europe they are distributed to a diverse network of companies, universities and research organisations. Funding through the European Union’s Framework Programmes FP7 and Horizon 2020 has played an important role in the formation of this ecosystem.

The essence of airborne wind energy is to replace material constraints (passive) by control algorithms (active). This is the great potential but at the same time also the challenge of the technology.

Using a lightweight tether in place of a tower and its foundation removes most of the mechanical constraints of the system. For this reason, control and optimization have already early on evolved into key research themes for AWE. In 2001, Moritz Diehl described the crosswind operation of a kite as an optimal control problem,15 expanding this later on the basis of a prestigious FP7 Starting Grant HighWind (2011-2017) awarded by the European Research Council (ERC). A first PhD dissertation entirely dedicated to control of AWE systems was defended in 2009 by Lorenzo Fagiano,16 who would become the most productive author of AWE literature.17 With the H2020 ITN doctoral training network AWESCO (2015-2018) control and optimization was complemented by modelling and simulation. Next to these more scientifically oriented projects, the EU awarded several H2020 projects to also support the industrial development of the technology: the Fast Track to Innovation (FTI) project REACH, as well as the SME Instrument projects AMPYXAP3, Nextwind, Skypull, EK200-AWESOME, AWESOME and the Eurostars project TwingPower.

The substantial growth of the R&D community in 2008 also intensified the need for an international platform to share and exchange results and results, to network and explore opportunities for collaboration. Accordingly, the first Airborne Wind Energy Conference (AWEC) was held in Chico, California, in 2009. Although this event was more a symposium than an international conference, it marked the starting point for a regular get-together of the international AWE community. The following group photos were taken at the AWEC’s in Stanford (2010), Leuven (2011), Hampton (2012), Berlin (2013), Delft (2015) and Freiburg (2017), with the two most recent events attracting each more than 200 participants.

Starting with the conference in Leuven, accepted abstracts have also been published in illustrated books of abstracts. The covers of these booklets, that are available free of charge online from the institutional repository of TU Delft, are shown in the following.

The complete bibliographic information is listed on the website of the AWEC 2019, which will be held in Glasgow from 15-16 October. Presentations at the conferences in Delft and Freiburg were video-recorded and deposited online together with the posters. As a result, the two conference websites present rather complete snapshots of the technology development status in 2015 and 2017.

At the AWEC 2011 in Leuven a petition to the European Parliament and the European Commissioners for better support of the technology was signed by 76 developers.18 Following several years of systematic support of the technology development, the European Union commissioned a study on the challenges in the commercialization of AWE systems to a consortium lead by Dutch consultancy company Ecorys. A stakeholder workshop at the EU headquarters in Brussels was held in July 2018 and key conclusions of the final report19 were that the AWES case from the perspective of EU industrial leadership is strong” but also that “the technology is still immature, and that it remains unclear whether the technology can ultimately reach cost-competitiveness”. As an important action the assessment team recommended to prove continuous operation of AWE systems and to deepen the insight into the resource potential and complementarity. Airborne Wind Europe was founded in 2018 as an association of European AWE industry and academia, with the objective to coordinate the commercial development activities and to establish joint working groups on important collaborative topics, such as safety and technical guidelines, airspace regulation, environmental impact and a sector-wide technology development roadmap. Regular meetings of the working groups have started in 2019.

It is interesting to note that AWE developed essentially in parallel to classical wind energy, with only little interaction between the two fields. While wind turbines are becoming the leading source of new renewable energy capacity in Europe, the US and Canada, with global installed power expanding from 17.4 GW in 2000 to 591 GW in 2018, the R&D activities in AWE have been carried by a vibrant startup community with many commonalities and strong ties to the unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) sector. First collaborations started to emerge after the research group of TU Delft was integrated into the section of Wind Energy in 2014 and Fort Felker, a former director of the National Wind Technology Center of NREL, started as CEO of Makani / X in 2015. The Airborne Wind Energy Conferences 2015 and 2017 have experienced increasing interest also from the wind energy community and, vice versa, also wind energy conferences are increasingly visited by the AWE community. For example, at the Wind Energy Science Conference (WESC) 2019 in Cork, at least 18 presentations were about AWE. During this conference, the European Academy of Wind Energy (EAWE) established a Airborne Wind Energy Committee to represent the academic community in Europe.

Presently pursued concepts

The presently pursued AWE technologies can be classified according to the following scheme.

At the top level we differentiate between electricity generation with a fixed ground station, with a moving ground station or directly on the flying device, requiring a conducting tether. Concepts using a moving ground station, such as a horizontal loop track or a carousel-type construction, are technically quite complex and still relatively far from realization. At the next level we distinguish between crosswind flight operation of individual tethered devices, flight operation aligned with the tether, without a significant crosswind component, and rotational flight operation of the entire device. For crosswind and tether-aligned operation, only the pulling forces of the flying devices are transferred to the ground station, while for rotational operation, an additional torque is transferred. Most populated is the combination of fixed ground station and crosswind operation. For continuous electricity generation, these systems combine a tether reel-out phase with a reel-in phase, which is denoted as “pumping cycle” and not unlike the thermodynamic cycle of a reciprocating engine, only that the energy is generated in the pulling phase and the cycle duration is much longer. A pioneering example for such a system is the kite power system of Delft University of Technology that was first operated in 2010.

This system consists of an inflatable membrane wing which is steered by a suspended, remote controlled cable robot, a single line tether and a ground station. A representative flight path computed with a dynamic system model is illustrated in the following diagram (kite not to scale).20

The corresponding time evolution of the mechanical power along two cycles is shown in the following diagram (left), with the blue area representing the energy generated during reel out and the red area the energy consumed during reel in. The dashed line indicates the average power. The power fluctuations during reel out are caused by the interplay of strong turbulence of the simulated wind field and the compensating reaction of the control system.

The cycles were simulated for a mean ground wind speed of 6 m/s. The mean wind speed at the operational height of the kite is higher and modeled with a logarithmic law. The diagram on the right shows the mechanical power curve of this specific pumping kite power system for the entire range of ground wind speeds. The symbol marks the operational condition considered in the left diagram and it is clear that this is roughly the point of nominal operation of this system, with the nominal mechanical power being around 12 kW. Because of the additional conversion losses the nominal electrical power of the system is lower.

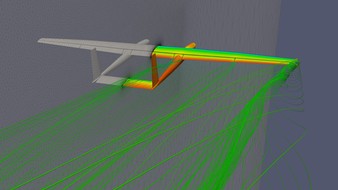

Multi-drone concepts and fully automated reliable take-off and landing, using VTOL and HTOL techniques, are challenging subjects that have been identified for future research.21 A detailed analysis and assessment of the different concepts has been presented by Cherubini et al.22 The largest commercial prototype in operation is the Makani M600, designed for a nominal power of 600 kW. The carbon composite wing with a span of 26 m uses 8 wind turbines for onboard electricity generation and automated vertical take-off and landing. A conducting tether is used to transmit the energy to the ground station.

Already early in the development, the company started the approval process with the FAA. Following testing in California and on the island of Hawaii, Makani has partnered with Shell to explore offshore operation in Norway.23

Not far behind is the Dutch enterprise Ampyx Power. Following extensive testing of their AP1 and AP2 development platforms, the company is currently assembling the AP3 with a wing span of 12 m and a power output of 250 kW.24

The aircraft is launched by catapult from a platform, which is also used for landing. The company is collaborating with national and European aviation authorities on the regulatory framework.25 It is planned to start operating the AP3 at a test site in Ireland, which is developed together with E.On.

While Makani and Ampyx Power both use tethered aircraft with conventional aerodynamic control surfaces, German company Enerkíte is developing a swept wing that itself functions as a single aerodynamic control surface, actuated by three tethers, each controlled individually from the ground station. The wing surface area of the EK200 will be 30 m2 and its nominal power 100 kW.26 A rotational mast is used for launching as illustrated in the following.

Because all electrical equipment is on the ground and the wing is bridled, its weight is relatively low such that the system can start operating at a wind speed as low as 2 m/s.

A nominal power of 100 kW is also the development target of TU Delft startup company Kitepower, which uses a flexible membrane wing that is controlled by a suspended, remote-controlled cable robot. This single-tether system configuration is illustrated in the following (the photographic visualization of the pumping cycle corresponds to the computed flight trajectory illustrated above).

The Leading Edge Inflatable (LEI) tube kite uses additional structural reinforcements to increase the maximum aerodynamic loading and lifetime of the wing.27 While the concepts of Makani and Ampyx Power aim at utility-scale electricity generation in offshore environments, the use of a lightweight flexible wings can be a decisive criterion for market segments in which high mobility, rapid deployment and low costs are crucial.

However, these are only 4 specific implementations of a diverse field of explored AWE concepts described by the classification scheme shown above. Some alternative projects by Kitemill, TwingTec, KiteX, Bladetips and Windswept are shown in the following.

Conclusions

Over the last 10 years, AWE has developed from a pool of conceptual ideas and some first small-scale experiments into a vibrant field of research and development, producing a diverse array of technology demonstrators ranging up to power outputs of several hundred kilowatts. Although there seems to be a trend towards rigid wing systems for large-scale generation, the field has not reached a state of convergence towards a specific concept. Several critical technical challenges have been mastered, such as automatic energy harvesting, reliable sensors and state estimation, as well as developing tethered aircraft and kites for aerodynamic load cycles that are far more demanding than those for conventional aircraft and paragliders.

Also the resource potential has been studied in more and more detail. A recent study shows that for most locations the average wind power density increases towards higher altitudes.28 By adjusting the average harvesting altitude continuously to the vertical wind profile, the fraction of time for which the system harvests at optimal conditions can be maximized. Depending on the available wind resource and the applicable regulatory limits, this technique should lead to a substantially higher capacity factor than achievable by conventional wind turbines.

But despite the technical achievements the economic potential of AWE has not yet been validated. None of the demonstrators has been operated for several weeks or months in a relevant wind environment. While the computer models to predict the power production have reached a high level of confidence, the actual uptime of demonstrators is still very limited. This can be explained by the fact that a flying object tethered to a ground station is a rather complex piece of technology, with many potential sources of failures affecting the overall reliability of the system. And when a component does not work as it should, the AWE system can not just be stopped in mid air.29 Remaining technical challenges are thus the full automation of the operation, including launching and landing, durable and lightweight flexible materials that can sustain a large number of load cycles, and a systematically increased reliability and ensured operational safety.

Addressing these challenges and proving the economic potential of AWE are the next steps lying ahead.

- Hermann Honnef: “High Wind Power Plants”. NASA Technical Translation NASA TT F-15,444, April 1974. PDF ^

- Erich Hau: “Wind Turbines: Fundamentals, Technologies, Application, Economics”. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, 2006. DOI ^

- Aloys van Gries: “Flugzeugstatik”. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, 1921. DOI ^

- Aloys van Gries: “Durch Drachen getragene Windkraftmaschine zur Nutzbarmachung von Höhenwinden”. Patent DE656194, 1935. PDF ^

- Aloys van Gries: “Improvements in or relating to Wind-driven Power”. Patent GB489139, 1937. PDF ^

- Aloys van Gries: “Moteur éolien”. Patent FR825476A, 1937. PDF ^

- Werner Schmidt, William Anderson: “Kites: Pioneers of Atmospheric Research”. In: Uwe Ahrens, Roland Schmehl, Moritz Diehl (Eds.) “Airborne Wind Energy”, Green Energy and Technology, Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 95-116, 2013. DOI PDF ^

- Hermann Oberth: “Verbessertes Drachenkraftwerk”. Patent Application DE2720339, 1977. PDF ^

- Hermann Oberth: “Das Drachenkraftwerk”. Uni Verlag, Dr. Roth-Oberth, Feucht, 1984. PDF ^

- Bryan W. Roberts: “Quad-Rotorcraft to Harness High-Altitude Wind Energy”. In: Roland Schmehl (Ed.) “Airborne Wind Energy - Advances in Technology Development and Research”, Green Energy and Technology, Springer Nature Singapore, pp. 581-601, 2018. DOI PDF ^

- Miles L. Loyd: “Crosswind Kite Power”. Journal of Energy, Vol. 4, No. 3, pp. 106-111, 1980 DOI PDF ^

- Miles L. Loyd: “Genesis of Crosswind Kite Power”. Presentation at the Airborne Wind Energy Conference (AWEC) 2010, Stanford, 28-29 September 2010. PDF ^

- Wubbo Ockels: “Laddermill, a novel concept to exploit the energy in the airspace”. Aircraft Design, Vol. 4, No. 2-3, pp. 81-97, 2001. DOI ^

- Roland Schmehl: “Critical Barriers for Airborne Wind Energy Systems Development”. Invited presentation at the Validation Workshop for the “Study on Challenges in the Commercialisation of Airborne Wind Energy Systems”, EU Headquarters, Brussels, 4 July 2018. ^

- Moritz Diehl: “Real-Time Optimization for Large Scale Nonlinear Processes”. PhD dissertation, University of Heidelberg, 2001. DOI PDF ^

- Lorenzo Fagiano: “Control of Tethered Airfoils for High-Altitude Wind Energy Generation”. PhD dissertation, Politecnico di Milano, 2009. PDF ^

- Anny K.S. Mendonça, Caroline R. Vaz, Álvaro G.R. Lezana, Cristiane A. Anacleto, Edson P. Paladini: “Comparing Patent and Scientific Literature in Airborne Wind Energy”. Sustainability Vol. 9, No. 6, Article-No. 915, 2017. DOI ^

- Wubbo Ockels et al: Petition letter to the members of the European Parliament and the European Commissioners. Leuven, 2 December 2011. PDF ^

- Karel van Hussen et al: “Study on Challenges in the Commercialisation of Airborne Wind Energy Systems”. ECORYS Report PP-05081-2016, Brussels, September 2018. DOI ^

- Uwe Fechner: “A methodology for the design of kite power control systems”. PhD dissertation, Delft University of Technology, 2016. DOI ^

- Simon Watson, Alberto Moro, et al: ““Future emerging technologies in the wind power sector: a European perspective”. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, Vol. 113, pp. 109270, 2019. DOI ^

- Antonello Cherubini, Andrea Papini, Rocco Vertechy, Marco Fontana: “Airborne Wind Energy Systems: A review of the technologies”. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, Vol. 51, pp. 1461-1476, 2015. DOI ^

- Arvid Nesse: “Application for establishment of temporary aviation obstacles”. Maritime Energy Test Centre (METCentre), Karmøy, Norway, 15 October 2018. PDF ^

- Michiel Kruijff, Richard Ruiterkamp: “A Roadmap Towards Airborne Wind Energy in the Utility Sector”. In: Roland Schmehl (Ed.) “Airborne Wind Energy - Advances in Technology Development and Research”, Green Energy and Technology, Springer Nature Singapore, pp. 643-662, 2018. DOI PDF ^

- Volkan Salma, Richard Ruiterkamp, Michiel Kruijff, M. M. (René) van Paassen, Roland Schmehl: “Current and Expected Airspace Regulations for Airborne Wind Energy Systems”. In: Roland Schmehl (Ed.) “Airborne Wind Energy - Advances in Technology Development and Research”, Green Energy and Technology, Springer Nature Singapore, pp. 703-725, 2018. DOI PDF ^

- Enerkíte GmbH: “Technical Data EK200”. Kleinmachnow, Germany. PDF ^

- Johannes Oehler, Roland Schmehl: “Aerodynamic characterization of a soft kite by in situ flow measurement”. Wind Energy Science, Vol. 4, pp. 1-21, 2019. DOI ^

- Philip Bechtle, Mark Schelbergen, Roland Schmehl, Udo Zillmann, Simon Watson: “Airborne wind energy resource analysis”. Renewable Energy, Vol. 141, pp. 1103-1116, 2019. DOI ^

- Moritz Diehl: “Airborne Wind Energy: Basic Concepts and Physical Foundations”. In: Uwe Ahrens, Moritz Diehl, Roland Schmehl (Eds.) “Airborne Wind Energy”, Green Energy and Technology, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 3-22, 2013. DOI PDF ^